For years, Rubyists (including where I work) have enjoyed the privilege of omitting parenthesis around method call arguments. Last week, we merged a pull request to our style guide revoking that privilege: parenthesis will become mandatory for all method calls with arguments.

Don’t let anyone fool you, Ruby is a complicated language. It’s syntax is full of quirks, pitfalls, and gotchas. It’s a minefield for newcomers and veterans alike. Despite that, it can be an elegant language; we just have to choose which subet of the language to use. We chose that this subset doesn’t allow omitting parentheses on methods which have parameters.

The discussion on wheter to enforce parentheses or not was a recurrent one. The arguments in favour of enforcing were generally around predictiblity, or removing the surface for mistakes. The arguments against cited that enforced usage of parentheses is inconsistent with Ruby in the wild, it’s not idiomatic. While arguments against have prevailed until now, the tipping point has been reached this week. Let’s examine what happened.

The Final Straw

Last week, I stumbled on the following piece of code in a slide deck describing a new feature:

|

|

Seasoned Ruby developers may understand the problem with this code, though it is far from self-evident. The issue is that block precedence is different for do/end and {} blocks. As a result, the two following blocks are not identical:

|

|

To understand the block precedence differences, we can group the expressions using parentheses to see what the VM will evaluate:

|

|

As you can see, they are not at all the same. The first case sends the return value of nodes.all? to assert, along with a block. The assert method does not expect a block, but also doesn’t fail: in Ruby, all methods will implicitly accept a block, regardless of whether they intend to or not.

With this in hand, I wanted to know how many other occurrences there were. I redefined assert to raise whenever it was called with a block, in order to know if the issue was a one-off, or systemic. There were 27 occurrences, out of which 7 didn’t pass once corrected. 27 mistakes counting only calls to assert. I haven’t checked further to see if other methods were unintendly called with a block that was meant for another receiver, as it’s pretty much impossible to script.

This find was the straw that broke the camel’s back. Something had to be done.

This example is (unfortunately) not the only problem with omitting parentheses. So many things can (and will!) go wrong.

What Else Can Go Wrong

Beyond inadvertently sending a block to the wrong method, many things can happen to Ruby methods. We’ll explore only the things that involve omitting parentheses. Every method accepting variadic or optional parameters is vulnerable to a slew of hard-to-detect issues. The following sections will show a few of these potential issues.

Disclaimer: Ruby developers like to omit parentheses moreso on what they call “macros” than on what they consider to be normal methods. In the code examples, “macros” will be over-represented.

Note about macros: there is no such thing as a language-level macro in Ruby, like you would find in C, Elixir, or Rust. Ruby macros are only social contracts, and have various definitions. Some people define it loosely as the methods that could reasonably be macros in other languages. This would include assert, has_many, extend and include, to name a few. Others would more formally define it as a method call with an implicit receiver where the receiver is a Module. Because I can’t possibly be expected to learn the list of all methods which fall in the first definition, and that the first definition is generally a superset of the second, I personally tend to subscribe to the 2nd definition.

Extra Trailing Commas

Consider the attr_reader method, on which it is generally accepted to not put parentheses. It’s variadic nature means that you can call it with any number of arguments.

|

|

The attr_reader method is just a regular method, and unlike in some other languages, it’s arguments can be the result of other expressions.

Unwittingly removing the last line change will not be a syntax error but may greatly impact the behaviour of the code:

|

|

The subtlety lies in the fact that def initialize will return the :initialize symbol, which will get passed to attr_reader as the 3rd positional argument, effectively making this code attr_reader(:a, :b, :initialize). Suddenly, the Foo class has an initialize attribute reader.

This could very well pass code review, because it is so subtle.

This extra trailing comma is only a problem because the arguments to attr_reader were not within parentheses; attr_reader(:a, :b,) would not result in the same problem.

Add parentheses.

Missing Trailling Commas

Extra trailing commas are not the only offenders; missing trailing commas are also problematic. Imagine a refactorig scenario that leads to this perfectly valid code:

|

|

The missing trailing comma makes @users_denied_from_blog_posts its own, valid expression which will effectively no-op. It is not sent to the can_access? method. Perhaps this will be caught by your test suite, perhaps it will not.

Again, using parentheses would’ve prevented the problem, making the code syntactically invalid.

Add parentheses.

Semantic White Space

Whitespace is sometimes semantic in Ruby, and this is generally around method calls, except if preceded by a paren, a comma, a backslash, a colon, and perhaps other punctuation. The simple fact that one has to memorize this rule (and that I don’t know it) is cause for concern.

These blocks are equivalent:

|

|

These are not, although both are perfectly valid Ruby:

|

|

Again. Add parentheses.

Learning Impediment, Cognitive Load

When developers are introduced to Ruby (and even more so to Ruby AND Rails), they have to learn a great many things. For reasons I still don’t understand, we teach them that somehow, attr_reader, extend, private, has_many, and so many others have special statuses; they’re not just regular methods. Yet they are. We’re actively hurting their learning experience, for legacy reasons.

Once they’ve learned that all methods are the same, they still have to remember and recall an ongoing list of which methods take parentheses, which don’t. This is no easy feat, and adds to the endless stream of decisions one has to make when writing code.

As a thought experiment, I was sent this example by a coworker, stating that they could not possibly be expected to add parentheses. The code is copied verbatim:

|

|

I must admit I’ve had great difficulty parsing that code. What gets sent to what? What chains on what?

The trick with this example is that the indenting is wrong (but copied verbatim). In fact, the first .and chains on the result of not_change {}, not the result of the previous to, as the indenting suggests. The second .and chains on the result of by(1). Writing this code with parentheses even with the wrong indenting makes this clear:

|

|

Yes, add parentheses.

Consistency and Readability

A large number of method calls have much more than one argument. Sometimes, they are long enough to span multiple lines. They are written sometimes adding parentheses, sometimes ommitting them, and some other times using \.

|

|

Some may consider that has_many(:posts) or attr_reader(:name) is off-putting, while others may not; it is a subjective matter. I think we can objectively agree that the above code is inconsistent. If for nothing else, our style guide should keep our code consistent.

Just add parentheses.

Editors

Today’s editors are pretty smart regarding parentheses. They can highlight matching sets of parens, select the internals, navigate to the end. This is all manual labour of parsing code that can be delegate to our tooling.

The Decision

Now that we understand many of the issues, we can devise ways to avoid them. We’ve found two ways:

- Add a set of new rules to our style guide that prevent all these cases

- Enforce parentheses everywhere

On the surface, option 1 may seem feasible. After all, if we understand all the problems, surely we can add enough rules to cover all of them. Maybe that’s true, maybe someone can write these rules, and be diligent enough such that none will conflict. That, however, serves to increase the cognitive load.

Option 2 is a simple rule. One rule. Occam’s Razor suggests it’s the best approach.

We believe that the benefits of enforcing parentheses significantly outweigh it’s downsides. Besides, it simplifies the way we write our software, even if just a little.

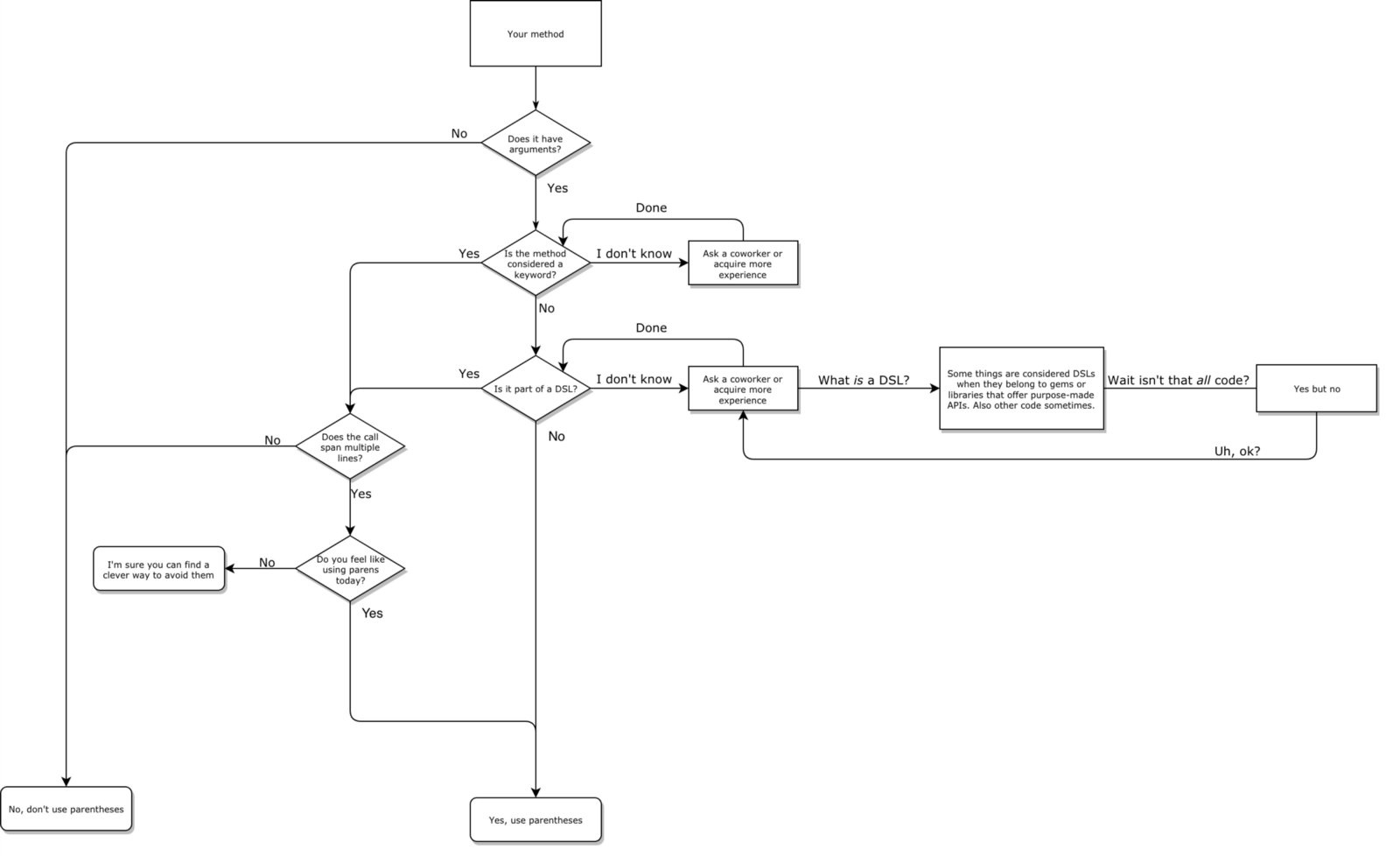

We went from a complicated, noninclusive decision tree,

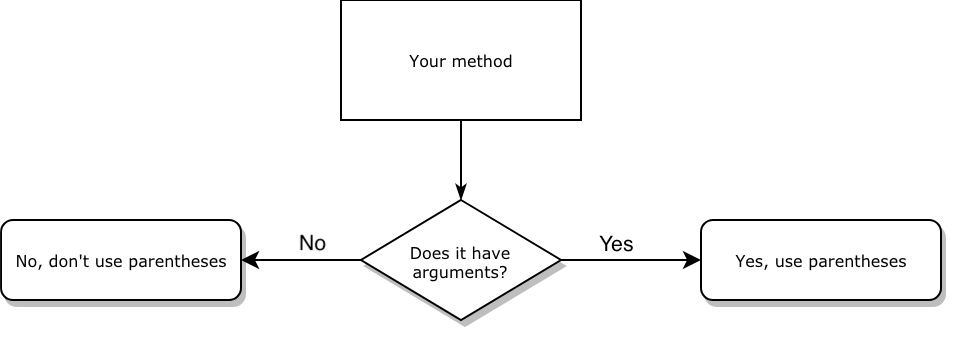

To a much simpler, more inclusive decision tree.

Final Considerations: About Idiomatic Code

In general, I believe following the community guidelines is preferrable. In light of all the evidence provided, I cannot hold that belief; I have to believe that writing safer and better software is more important than following the style used by others.

Idiomatic Ruby once was the Seattle Style. I don’t see anyone arguing we should go back. The idiomatic style is just the style which is in vogue at the moment. And it changes, all the time, as new informations, new ideas, new authors come to light. We can be the forbearers of this new, idiomatic style.