For the past year, my team has been working on a project that exposes a GraphQL API, and, since we’ve been doing things quite differently than the rest of the company, I figured some of our ideas might be worth sharing. We’ve been using the graphql-ruby gem, and even though it doesn’t lend itself well to unit testing, we’ve insisted on writing unit tests. What’s more, we’ve also used Sorbet to prevent other categories of errors; in fact, most of our code is using typed: strict! In this post, I’ll share why we went out of our way to do this, and how it can be done.

If you don’t like boilerplate code, beware, the quantity of boilerplate required is staggering!

Note: for the purpose of this post, I will assume that you are familiar with the Sorbet and GraphQL syntaxes.

Primer

I want to start by explaining some of the challenges we had in designing our GraphQL API. The project we’re working on is an integration point for many other teams and projects of different domains, most of which we don’t control. However, these domains need inputs from the API, and they need to expose data of their own. As a result, my team can’t be expected to know everything going on in the other domains, just as it’s unrealistic to expect other teams to freeze their code.

Implementations will change. Methods will be added and removed. Classes will be renamed. Refactors will happen. For our project to be successful, we need to give developers (both internal and external to the project) the agency to make changes, and the confidence they are not compromising the stability of the API.

API

Simplistically, the goal of the API is to:

- accept inputs from the client

- map inputs to domain objects

- invoke a procedure with the domain objects as inputs, and receive a domain object as outputs

- map the returned domain object into an API output value

- return the output value to the client

Our goal was to provide a high level of confidence that each of these steps works as expected, at the lowest cost possible in terms of dev time and feedback time.

Why Unit Tests

The graphql-ruby section on tests suggests relying on unit testing the domain, and integration testing the API. Integration testing is great, but it isn’t enough to check that domain types map correctly to API types, that API input types map correctly to domain types, or that the correct procedures will be invoked. Our API contains many, many types, and building tests that cover the cardinality of all possible type mapping would make for a very slow test suite. Unit tests don’t suffer from this problem, especially when paired with static analysis.

Unit tests allow us to check that all tested values will be mapped as expected.

Why Static Typing

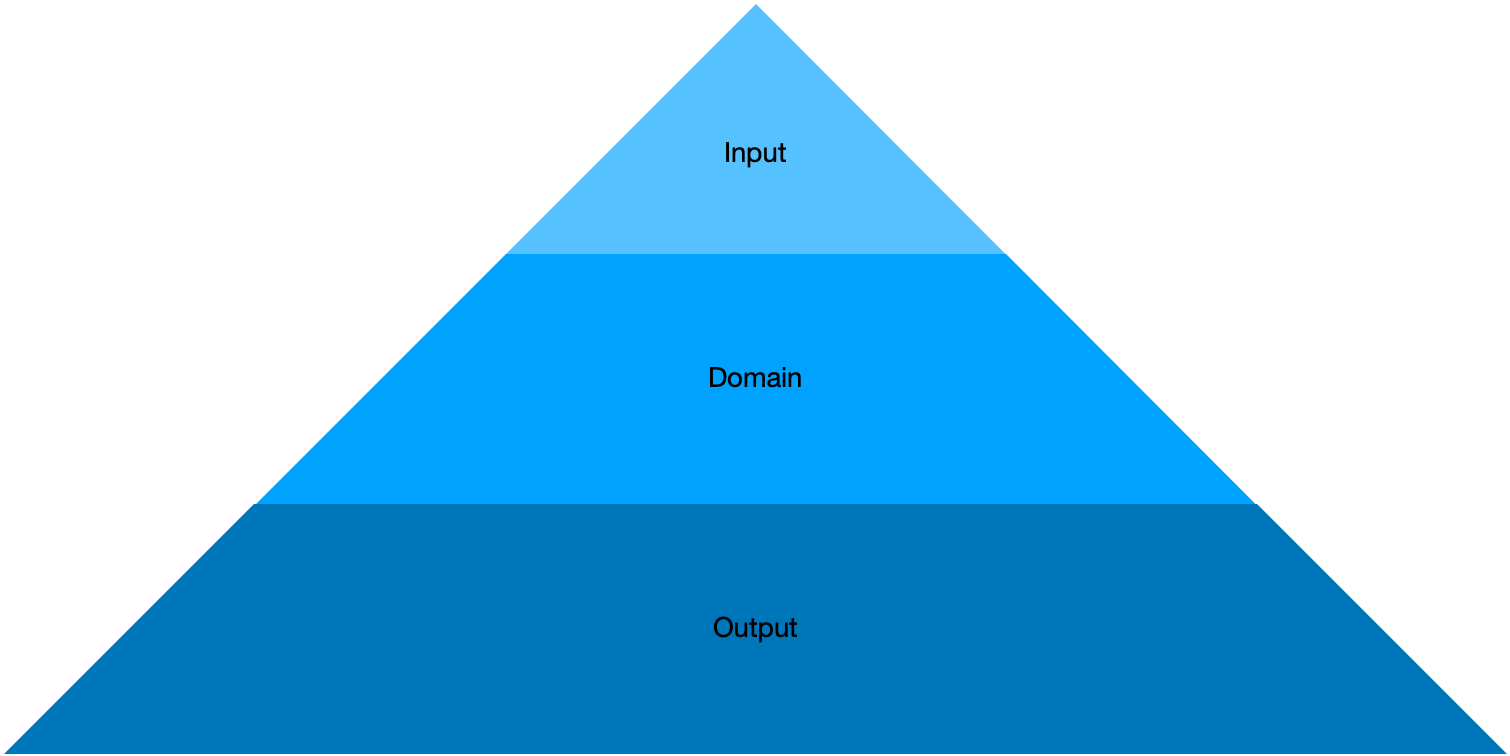

I like to think of values used in APIs as a pyramid, in which the domain must be able to support all input values, and the output must support all the domain values.

For example, our API could use these types, where all types are identical:

Input = Integer

Domain = Integer

Output = Integer

It’s also possible to use an actual pyramid of types:

Input = Integer

Domain = Integer | Float

Output = Numeric

However, using types that can’t naturally represent the values they must support will require constraining. For example, if we used the following types, the API would require another way to constrain the values, often resorting to errors:

Input = Float

Domain = Integer

Output = PositiveInteger

In GraphQL and Ruby, constraining is quickly required, because GraphQL’s Int type is limited to 32 bits, whereas Ruby’s Integer type is not.

In practice, it will not always apply, but starting with that mindset will help us understand how our types are constrained.

Static analysis allows us to verify that each layer can support the values representable by the layers above it. This has been especially useful to catch changes in the domain that can’t be mapped by the API, because the tests don’t necessarily exist. For example, this change:

|

|

We haven’t been able to write tests of our API that would catch this change and alert us that Output’s type must also be changed. Static analysis catches this easily.

Practical Example

For the rest of this article, we’ll be working on a small API. Suppose there’s another team that owns the entirety of Messages, and yet we still need to allow interacting with Message objects in our API.

The domain is simple enough: we can create new messages using Domain::Message.create with an instantiated Domain::Message, and we will get back a Message object. The code below is the entire public API they expose.

|

|

Note: The code contained in this post has been made available in a separate repository on GitHub, and each commit corresponds to progress in this post.

Since we don’t know anything about Messages and we’re short on time, we’ll just expose an API that is a direct translation what’s offered internally. This is what the GraphQL definitions would look like, before we start implementing resolvers.

|

|

This will generate the following GraphQL IDL:

|

|

Testing Inputs

Input types need to be mapped to domain types, and we would very much like to test that they can be mapped correctly. The graphql-ruby gem allows the definition of a prepare method that does this mapping. Unfortunately, for Sorbet’s benefits, we’ll also need to define the fields as private methods. The upside is that we’ll also benefit from runtime type checking (albeit incomplete) in addition to static analysis.

|

|

Unfortunately, adding tests to Api::MessageInput#prepare requires a bit of boilerplate to instantiate the objects. We can nonetheless test that all inputs will be mapped correctly.

|

|

Running tests show that this works as expected.

$ rspec

Api::MessageInput

#prepare

can map to a Domain::Message when all values are present

can map to a Domain::Message with a nil from_name

2 examples, 0 failures

Testing Return Values

Testing return values will require a lot more boilerplate than for inputs.

The graphql-ruby gem instantiates GraphQL::Schema::Object values for every object passing through it, which has the benefit of being convenient if you’re abiding to all its recommendations, but wasteful if you aren’t. Spoiler: we aren’t. Instead we’d rather define functions that map from the domain objects into API objects, making them easier to test.

To do that, we’ll delegate one method per field to a singleton object. In our project we chose to have a Resolvers module per GraphQL class, with one singleton method per field.

Pure delegation isn’t going to work either, as we need to pass the underlying domain object. Luckily, Ruby has refinements which allow adding a delegate_to method that will not be exposed externally.

Note: In our project we’ve also found that we needed to pass the context in some situations, mainly for dependency injection. context will not be needed in this example, but I’m going to include it nonetheless, in case someone is tempted to try this approach on their own project. Our implementation is much longer and contains many verifications to remove affordances: the field must exist, the method must exist on the delegate, its arity must be correct, etc. I can provide a more thorough implementation if there’s interest.

|

|

Our implementation of the Resolvers module defines a lot of boilerplate, and I wish this pattern was supported directly in the graphql-ruby gem: using delegates instead of instantiating unnecessary objects would put less pressure on the garbage collector.

|

|

The Sorbet annotations in this code are enough for Sorbet to notify us if we ever use a method that doesn’t exist (or no longer exists!), or if the types don’t line up like we expect them to.

This code also makes it easy to test that the Resolvers module can map from a domain type to types that GraphQL can represent.

|

|

And run it!

$ rspec

Api::MessageInput

#prepare

can map to a Domain::Message when all values are present

can map to a Domain::Message with a nil from_name

Api::Message

#from_name

returns the message author's name

can be nil

#content

returns the message's content

Finished in 0.00612 seconds (files took 0.33929 seconds to load)

5 examples, 0 failures

We chose not to test the actual Api::Message object (since it performs no work). Instead, we have another, separate test that makes sure all boilerplate and wiring is done correctly. This test will be out of the scope of this post, however. While it isn’t exactly fast, it covers the entire schema in roughly 500ms, which is faster than the average integration test in our codebase.

We will implement and test the MutationRoot in the same way. There are two differences here, however. First, the object delegated by the MutationRoot has no semantic value, so we’ll just treat it as a BasicObject. Second, the graphql-ruby gem passes the field arguments as named parameters, so we’ll need to define them explicitly. Finally, we’ll define _context explicitly, only because using a splat (*) could cause confusion with named arguments.

|

|

Similarly to Api::Message, we can write unit tests for the Api::MutationRoot.

|

|

Note: If you’d rather not use expect, you can use the context object to allow dependency injection. We do this extensively and it works well.

$ rspec

Api::MutationRoot

#message_create

calls Domain::Message with the message

Finished in 0.0111 seconds (files took 0.34917 seconds to load)

1 examples, 0 failures

While we’re at it, let’s see what Sorbet has to say.

$ srb tc

No errors! Great job.

Sweet! However, this isn’t very surprising, since we haven’t told Sorbet about the links between the API classes. For example, it would be possible for Api::MessageInput#prepare to return a value that’s incompatible with message_create.

|

|

Sorbet isn’t able to tell us that this produces an invalid value.

$ srb tc

No errors! Great job.

Luckily, our test suite would catch this error, but it would be even better if Sorbet could tell us. Let’s do just that.

Adding Types

The problem we currently have is that Sorbet doesn’t understand the coupling that exists between the different pieces of the domain and API. Adding those will require even more boilerplate, but it’s achievable, and, in my opinion, definitely worth it.

Here’s how we managed to do it:

- Input types define a

PrepareTypetype alias, which is the return type of thepreparemethod. - Output types define an

ObjectTypetype alias, which is the type of theobjectvalue they receive. - All inputs and outputs can be either

PrepareTypeorObjectType, or primitive types which GraphQL understands.

On Api::MessageInput, we will define a PrepareType type alias, and use it (rule #1).

|

|

On Api::Message, define an ObjectType and use it (rule #2).

|

|

Finally, on Api::MutationRoot, we’ll use the type aliases (rule #3).

|

|

With those changes, our types are properly coupled together, and applying the same erroneous changes as before (prepare returning Integer) will produce errors:

$ srb tc

sorbet.rb:236: Expected Domain::Message but found Integer for argument message https://srb.help/7002

236 | Domain::Message.create(message_input)

^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

sorbet.rb:16: Method Domain::Message.create has specified message as Domain::Message

16 | params(message: Domain::Message)

^^^^^^^

Got Integer originating from:

sorbet.rb:235:

235 | def message_create(_obj, _context, message_input:)

^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

Errors: 1

Success!

Now let’s be real for a second. Our tests had also caught this problem, and the code required for static analysis added a TON of boilerplate, and you may be wondering: is it really worth it? If you’re used to having static typing or swear by unit testing, you may have already answered “yes”, but it’s entirely normal to remain skeptical. In the next section, we’ll see why I consider all this boilerplate worthwhile, and which situations make it useful.

Changing Things

Recall that the Domain::Message is owned by another team. They will not necessarily tell us when they make changes, in part because they may not know that we’re using their APIs. The boilerplate written in the previous section was an attempt to force them into knowing by coupling our API to theirs.

When we design software, we try to avoid breaking changes, but from what I’ve seen, they’re almost inevitable.

In this section, we’ll see how 2 types of breaking changes can be caught by Sorbet that would not have been caught by tests: when an input type becomes narrower (accepts less values) than it was before, or when an output type becomes wider (contains more values).

Input Narrowing

In some cases, it may make sense to narrow the inputs of a method. For example, maybe anonymous messages have been removed from the scope, and the team wants to narrow the input type of fromName to just String.

|

|

It’s entirely possible that, writing integration tests only, we wouldn’t have written a test for fromName = nil. Luckily, we wrote unit tests, so this change wouldn’t go unnoticed, and it would signal to the domain team that they need to communicate with our team about these changes.

$ rspec

Api::MessageInput

#prepare

can map to a Domain::Message when all values are present

can map to a Domain::Message with a nil from_name (FAILED - 1)

Api::Message

#from_name

returns the message author's name

can be nil (FAILED - 2)

#content

returns the message's content

Api::MutationRoot

#message_create

calls Domain::Message with the message

Finished in 0.01886 seconds (files took 0.33419 seconds to load)

6 examples, 2 failures

Even in the event that we had omitted to write any test, Sorbet would still catch the problem.

sorbet.rb:92: Expected String but found T.nilable(String) for argument from_name https://srb.help/7002

92 | content: content,

93 | from_name: from_name,

sorbet.rb:25: Method Domain::Message#initialize has specified from_name as String

25 | params(content: String, from_name: String)

^^^^^^^^^

Got T.nilable(String) originating from:

sorbet.rb:92:

92 | content: content,

93 | from_name: from_name,

Errors: 1

Output Widening

Sometimes, the type of the return value will need to be widened, to accomodate for changes. It’s next to impossible to design tests that will preempt errors stemming from this kind of changes, but static analysis will find them without a problem.

For example, imagine that, in certain scenarios, Domain::Message.create will not be able to return a Domain::Message. This could happen if the datastore is overwhelmed, for example. The domain team choses to instead buffer the write, and return a Domain::Pending value, indicating that the write will happen at a later time.

|

|

Once again, Sorbet will find the problem and tell us that the return value of Domain::Message.create is incompatible with Api::MutationRoot#message_create.

$ srb tc

sorbet.rb:143: Returning value that does not conform to method result type https://srb.help/7005

143 | Domain::Message.create(message_input)

^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

Expected Domain::Message

sorbet.rb:142: Method message_create has return type Domain::Message

142 | def message_create(_obj, _context, message_input:)

^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

Got T.any(Domain::Message, Domain::Message::Pending) originating from:

sorbet.rb:143:

143 | Domain::Message.create(message_input)

^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

Errors: 1

How to handle this kind of change will ultimately be the author’s decision, but I wanted to briefly touch on union type in graphql-ruby and how to handle them in Sorbet.

For our example we want to expose the Pending message creation in the GraphQL API, and so we need to introduce a Api::MessagePending type to represent it.

|

|

We also need to change the return value of messageCreate to be a union of Pending and Message, which we can call MessageCreateResult. Luckily, the union types in graphql-ruby make it easy to add Sorbet, so we won’t need to rely on the Resolvers module like before. We just need to make sure that its ObjectType is the union of all ObjectType of its possible_values. In the resolve_type method, we can even make use of Sorbet’s exhaustiveness checking with T.absurd.

Our resolve_type will return a tuple of two values. The first value of the tuple is the GraphQL class that contains the mapping functions. The second values allows unwrapping the value. This isn’t super useful in the current code, but if we were using wrapper objects (like a Result type), it would simplify the code a lot, since members of the union wouldn’t need to share one type.

|

|

|

|

Sorbet will understand this correctly, and notify us if the return type of Domain::Message.create is once again changed.

$ srb tc

No errors! Great job.

Conclusion

In this post, we’ve seen a few ways in which we can define GraphQL schemas in Ruby, unit test them, and add Sorbet static analysis. We’ve seen a few ways in which unit tests and Sorbet would be able to catch breaking changes, which would be next to impossible to catch using integration tests only.

I hope that you’ll now consider annotating your GraphQL schema with Sorbet and benefit from its much faster feedback loop, as well as its ability to reveal bugs that are impossible to find only with tests.

Finally, if you are or you know a contributor of graphql-ruby, can you add the possibility to delegate fields to an object and skip the instantiation of GraphQL::Schema::Object, pretty please!